Let My Hands Remember this Swedish Soil Forever

A Reflection on WWOOFing Abroad

Brett LeVan (she/her) ’26

When people ask me what I did this summer, I tell them I volunteered on a farm in Sweden. And somehow, though this is the truth, to sum up my experience in one simple sentence feels like a lie, even a desperate betrayal.

In June, I boarded flight UA 9458 in Denver and flew to Munich, Germany and then to Stockholm, Sweden alone. When I first arrived, people asked me why I chose Rosenhill, or why I chose Sweden in general. I told them the truth: I didn’t want to be in the United States, so I picked a country and found a farm. I was desperate to leave the United States and thought I was finding a place to survive for two months. I realize now how naïve I was.

“I didn’t want to be in the United States, so I picked a country and found a farm”

From just before Midsommar, the annual Swedish celebration of summer usually held around the date of summer solstice, through just before peak apple season in August, I volunteered at Rosenhill, a collective farming community set amongst the forests and rolling fields of Ekerö, an island just outside Stockholm, Sweden.

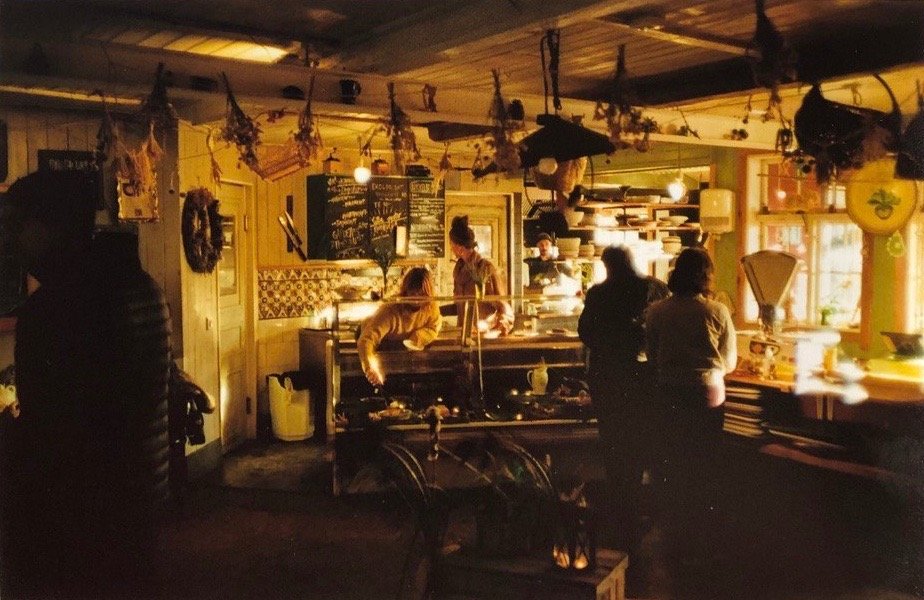

Rosenhill is an organic vegetable, flower, and fruit farm, an apple musteri (juicery), and a Swedish café and restaurant. An oasis to say the least. Reducing to words the life I lived feels impossible and daunting; Rosenhill changed my perspective of home, community, and what I thought was possible in life.

I knew prior to this experience the importance of volunteering, how organizations like WWOOF (World-Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) and World Packers offer accessible opportunities for people to travel and immerse themselves in foreign and impactful places. I did just that, I volunteered at Rosenhill as a WWOOFer — living, eating, and learning in exchange for 30 hours of work each week, though I presume I worked much more.

Individuals from The Netherlands, France, Sweden, Germany, South Africa, Chile, Japan, the United States, and Belgium worked with me at Rosenhill over the duration of the summer. More than a dozen paid seasonal farm workers, and dozens of fellow WWOOFers like myself arrived and departed, some staying two weeks, others much longer. As a long-time WWOOFer, I observed the ebb and flow of people, the massing of experiences, our collective footprint on that tiny little patch of earth, and the ways individuals connect within a group despite being from five different continents.

“As a long-time WWOOFer, I observed the ebb and flow of people, the mass of experiences, our collective footprint on that tiny little patch of earth”

I awoke each morning in the shell of a converted blue bus named “Bob the Bus.” The front driving space still intact and original, the body of the bus was filled with a couch, drawers, a set of bunk beds, and my twin mattress set on top of the old table. My body was forced to sleep at dusk and wake in daylight. I allowed the insects to create a home around me and for the crows and farm birds to startle me awake.

Much of my first week at Rosenhill was spent learning the rhythm and routine of 30 individuals living in community with each other. I arrived on a Monday, and the Midsommar celebration was on Friday. I was dancing, drinking schnapps, and celebrating like I had known those people my whole life. Buckets of fresh flowers were picked and placed on the big communal table in the yard which often held our evening meals.

On Friday morning, after decorating the meal area with fresh bouquets of flowers picked from around the farm and birch trees cut the evening before, we sat dressed in white and pastel colors making our Midsommar crowns. At first I did not know how to manipulate the birch leaves into a crown shape or how to tie each fragile flower onto it to make my Midsommar crown similar to those around me. But as the crowns came together and as we placed them on our heads, we looked beautiful. That day was magic – more than magic but I have learned some feelings cannot always be expressed adequately into words.

My Midsommar crown sat in my blue bus for the entirety of my summer; it dried in the Swedish sun along with another crown left to me from a Dutch boy – the crowns unintentionally dried together. Now, after carefully sneaking them through the Denver International Airport customs, the dried Midsommar crowns sit in my dorm room here. I am careful to touch them because just like I am desperate to preserve every feeling from this summer, I am hopeful the dried flowers can also be preserved forever.

At the beginning of each work week, WWOOFers would be assigned into three groups with any of the three gardeners — Ale, Hannah Maria, or Olja. Ale, who was from Chile, oversaw the tomato greenhouse, harvest day, and the vegetable shop. Hannah Maria, who was from Sweden, oversaw the veggie fields. And Olja, who was from The Netherlands, oversaw the flower field. All three of them taught me about vegetables, flowers, gardening, community, celebrations, seasons, and friendships. Individually and collectively, they encouraged me to be ever present with lessons the soil can teach me.

Mismatched-eclectic furniture offered a place of rest for each of us on the farm; from the assortment of different chairs for customers, all the mismatched plates in the kitchen, or the “junk yard chic” nature of all the different buses and trailers we lived in. Throughout the farm, I adopted one particular blue couch in the barn under a gallery wall of oddly shaped paintings. This particular couch sat adjacent to the ever-burning wood fire stove, and at the end of a long day of weeding or harvesting I would plop down waiting for one of my friends to come and join me. I often sat on my phone listening to the chatter of Swedish around me, and waiting for the few words I recognized or anticipating when a customer would approach me, and I would get to say “jag pratar inte svenska” (I don’t speak Swedish). While I did not speak Swedish, people would often be able to speak to me in English, the communal language on the farm.

One evening in particular, after a long day of work, a dozen or so of my fellow workers had gathered around the fire with a guitar to sing. I had been lying on my favorite blue couch slowly dozing off to sleep listening to each strum of the guitar when I heard the opening chords to “Country Road Take Me Home.” I was the only individual in the room from the United States and I was jerked awake from the sound of such a nostalgic song. I stood up and walked over to the fire and sat with them as we sang each word. It was as if there was no difference between where I called home and where everyone else did. It was like there was no country border between any of us, despite so many nationalities present.

I quickly realized my position on the farm as someone from the United States. Whether it was Ale reminding me that I cannot call myself American because people from South America are also American. Or if it was the frequent apology from fellow workers that I was from the United States. I found myself reminded daily of how stark of a contrast my life here in the United States is to that which I lived this summer. I was embarrassed with my response when people asked me how much I pay for college when they quickly reminded me they often attend for free. I valued the fact that the people who worked alongside me at Rosenhill chose to be there with or without being paid. Collectively, it felt like even those who were paid, knew their pay wouldn't be as much as other places so that WWOOFers like me could experience Rosenhill.

Though I decided I wanted to go to Sweden last October, when spring came and it was time to purchase my plane ticket to Europe, I was reluctant to commit because I felt like I needed to stay home and work. I felt like I needed to earn money, I realize now I was paid this summer, not in cash but in knowledge and experience – something money can never buy.

My previous mindset, a mindset rooted in consumerism and self-indulgence, has started to seek nuances of seasons and communal bonds that cannot be purchased or traded, but can be nurtured and treasured.

My purpose on the farm changed when I found where I thrived. My peers saw a fire within me before I even noticed. I gained confidence I didn’t know I had. I learned from Ale by accompanying her with the vegetable shop and harvest day. Together Ale and Maud, one of the chefs in the restaurant who was from The Netherlands, would go over what vegetables were needed in the kitchen for the week, then on Thursdays, which were harvest days, myself and the WWOOFers in Ale’s team that week would go out and harvest.

We harvested enough for the kitchen and for the vegetable shop, and then with the help of others, I would wash and bundle the vegetables and place them in the shop for customers to purchase. By the time I left, I found where I belonged. I had responsibilities with the vegetable shop and harvest day that I could have never dreamed of having at the beginning of my experience.

Each new day my morning chore was setting out the produce in the vegetable shop after putting the produce away in the cool room the evening before. The Mangold knippes (bundles) would sell the quickest at 30 kr per bundle. So, as my peers were sweeping the barn, doing morning dishes, or cleaning the restrooms before customers arrived, I would walk out to Hannah Maria’s veggie field with my gardening shears and harvest dozens of fresh vibrantly colored Mangold leaves. Each Mangold knippe had 10 leaves.

Here in the United States, Mangold is better known as Swiss Chard, just like Cilantro is called Coriander in Sweden. I learned the Swedish names of vegetables and labeled the vegetable shop each harvest day along with the price in krona SEK.

Every Monday the restaurant and café were closed, it was one of the two days off for the WWOOFers and gardeners at Rosenhill. I often took the hour-long trip into Stockholm with other WWOOFers or walked 20 minutes to the secret beach on my days off. Each Monday while the farm was closed to customers, the chefs and bakers made the pastries and cakes for the café to sell that week. The sourdough bread was made almost daily in the bakery. We ate it each morning at breakfast, and it was included in many of the restaurant's dishes. The offering said before each lunch and dinner communicated gratitude for all that arrived and existed at Rosenhill:

“Jorden har oss detta gett

Solen det i ljus berett

Kära sol och kära jord

Er vi tachar vid vård bord.

Välsignad vare maten, skål!”

“The earth who gives to us this food

The sun has with light ripened

Dear sun and dear earth

To you with thanks by the table

Bless the food, cheers/skål!”

While at first I was uncertain of my decision to spend my summer abroad, if I can offer anything, it is to venture to a place for an extended period of time. Cross cultural experiences demand time to be fully experienced. And I hope you find that home is a feeling rather than a place – having had to establish a sense of belonging at boarding school, summer long camp, and two hometowns, my perception of home has always been a bit skewed but now I am even more uncertain.

Someone on the farm once described Rosenhill as a place people go to when seeking “more” in life — I couldn’t agree more. The people who accompanied and nurtured me this summer went to university and earned degrees, many of them worked previous careers, but ultimately, they found and returned to Rosenhill. Many of the seasonal workers first started at Rosenhill as WWOOFers and now return season after season. A space so full and rich gives a reason to return. Yet, a space full of different individuals and backgrounds comes with conflict and hard work to make such a space a community. The continual return to Rosenhill is a reflection of more than just intentional living but proof Rosenhill is a place which gives “more” to its community than any place before it.

I will hold this experience and this place within my fingers, within the cracked calluses on my feet, within my veins, and within my soul. For the community at Rosenhill, the people who impacted me, the soil which has soothed me and the fire that now burns deep within me is a reflection of humanity, passion, and a call to live more intentionally. I now recognize myself as a constantly evolving individual, shaped by the people who influenced me at Rosenhill.

I yearn to return, to harvest the vibrantly colored Mangold leaves, and to feel the pull of carrots as they become loose in the Swedish soil. My connection to the earth through my hands isn’t necessarily new to me, but the knowledge I learned in Sweden has deepened and expanded it. I hope I can offer a new perspective — when we follow the harvest and listen to what’s under our feet, previous understandings can be challenged. I found a space which made saying goodbye so incredibly hard. The intimate conversations and the people I learned from helped me realize I can live a life of intentionality outside of what I knew was possible. A feeling of home is stronger than any coordinates on a map and when people ask me where I feel most rooted or most in community with those around me, I shall tell them about Rosenhill.

I hope each person has their own version of a Rosenhill. Whatever it is, I hope you will venture to a foreign country, work on a random farm or another collective community, and find a place that shows you what living more fully means. Next summer you will hopefully find me back at Rosenhill, but until then, let my hands remember that Swedish soil forever.